My original data project for the Digital Praxis Seminar Fall 2016 consisted of collecting tweets with feminism-related hashtags and/or keywords in Korean, along with some rudimentary analysis. Below is the description and results.

Introduction

Gender inequality is a persistent condition of the South Korean society. A few numbers might give a rough idea of women’s status in the country:

- In 2013, women were paid 30% less and were employed 23% less than men. (For comparison, the U.S. gender wage gap in 2013 was about 18%)

- The most recent legislative election in 2016 resulted in the highest ratio of women in the National Assembly’s history: 17%

Violence against women is also frequent. According to the NGO Korea Women’s Hot Line, at least one woman was murdered by her partner every 4 days in 2015, only counting those reported in the news. The Korean government’s official statistics show that among victims of violent crime, around 30% were women in the 90s; however, this number has increased to more than 80% in the 2010s, pointing to an aggravation of misogynic tendencies of the society.

The misogynic tendency of the South Korean society has been the subject of a growing national discussion, one that I have been following online. One important instance in the discussion was the Twitter hashtag #나는페미니스트입니다 (lit. “I am a feminist”), which first appeared on Feb 9 2015.

The hashtag appeared after a series of comparison between the Islamic State (IS) and feminism. One South Korean male teenager went on to join IS, after tweeting out “However, the current era is the era that male are being discriminated against” (reflecting a rather common sentiment among Koreans) and “i hate feminist So I like the ISIS.”

A male pop columnist then ignited the hashtag, with a magazine article titled “Brainless feminism is more dangerous than IS,” arguing that feminism is confrontational and divisive, which gives rises to such reactions as the aforementioned teenager’s decision.

In response to such an argument, Twitter users started using the #나는페미니스트입니다 tag in order to self-identify as feminist, and also to problematize the negative social construction of the term. I think this movement was an important moment which eventually led to feminist discourse, which I feel was not significantly addressed in mainstream media or in my own social network, take on the role of a more urgent agenda. This is why I was interested in archiving these tweets; looking at the entirety of the tweets, which I experienced in small chunks in real time, might provide a better insight to what happened.

The data

First, I collected the tweets tagged with #나는페미니스트입니다, along with its variants, #나는_페미니스트입니다 and #나는페미니스트다. Since the Twitter API is restrictive when it comes to searching old tweets, I had to rely on Twitter’s web search interface which allows search from the beginning of the service. One thing about this interface is that only a small number of tweets appear at first; in order to see the rest, one has to scroll to the bottom of the page, which then makes the browser load more tweets. Another caveat (which I did not verify, but saw mentioned in several places) is that web browser will stop loading tweets once the number tweets loaded on the page goes above 3,200. In order to reduce the risk of not retrieving all existing tweets because of this caveat, I segmented my search by using the SINCE and UNTIL operators: this allowed me to search day by day, minimizing the tweets that each search will return.

I decided to collect one year’s worth of data using this specific search query. I wrote a Python script using the Selenium WebDriver and BeautifulSoup packages; the script visited Twitter’s web search page using my search query, scrolled down to the bottom of the page, checked if the scrolling down triggered more tweets to appear, then saved the tweets and metadata parsed from the source HTML, iterating over each day.

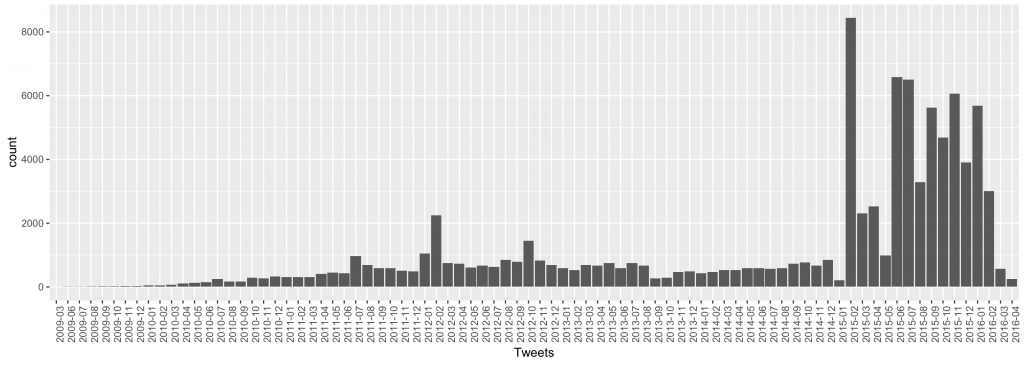

Over the span of the year, the hashtag was used in roughly 5,000 tweets. It doesn’t seem like a particularly large number, but I think it had the effect of opening up related discourse. I repeated the search over a longer period of time, with the search query “페미니스트 OR 페미니즘” (lit. “feminist OR feminism,” returning tweets that have either terms in it). This search returned nearly 60,000 tweets during the one year after the first use of #나는페미니스트입니다, compared to 33,700 tweets from 2009 (when Twitter started its service) until before the hashtag appeared.

This is evident in the visualization I drew using R, displaying the volume of the tweets per month (total ~90K): there is a dramatic increase of tweets that include “페미니스트” or “페미니즘” in February 2015. For this observation to be more valid I would need to take into account the total volume of tweets written in Korean, regardless of subject, during these periods. However, the drastic change seems to support my hunch.

In addition, I used the unique ids of tweets with hashtags in order to retrieve from the Twitter API a more comprehensive tweet data.

Analysis

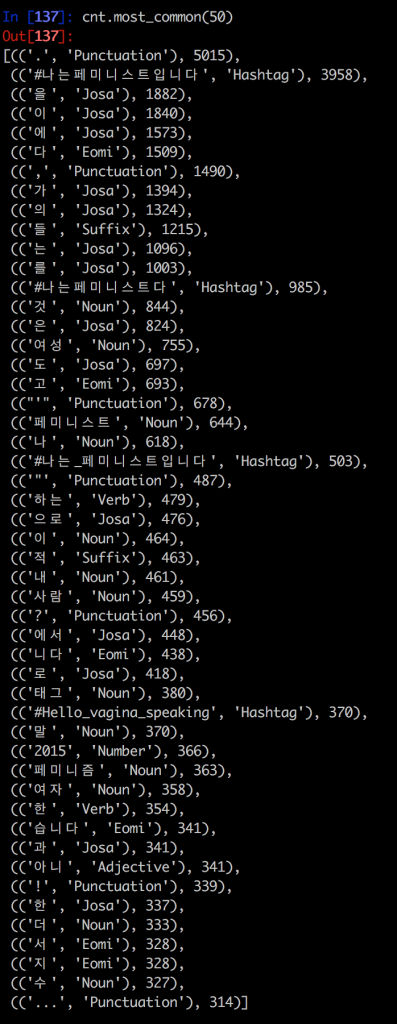

I conducted a basic text analysis of the 5K tweets with #나는페미니스트입니다 and looked at frequently used terms. Using Python’s re and codecs packages, I grabbed the text of each tweet cleaned the data of user handles and weird unicode (which is necessary since I am dealing with a non-Latin language). Then, using the KoNLPy package, which is an NLP tool for the Korean language, I tagged each morpheme with the corresponding part of speech.

A quick list of most common morphemes returns the following list:

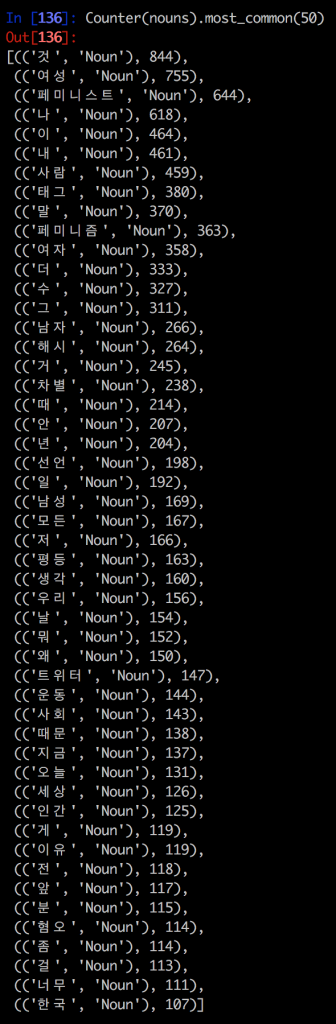

However, there is a lot of unnecessary things here. For starters, hashtags and punctutations; also, the parts of speech ‘Eomi’ and ‘Josa’ exist largely for grammatical purposes—hence the adjacent list of common nouns (written with English translation below)

[((‘것’, ‘Noun’), 844), (Thing)

((‘여성’, ‘Noun’), 755), (Female)

((‘페미니스트’, ‘Noun’), 644), (Feminist)

((‘나’, ‘Noun’), 618), (Me)

((‘이’, ‘Noun’), 464), (This)

((‘내’, ‘Noun’), 461), (My)

((‘사람’, ‘Noun’), 459), (Person)

((‘태그’, ‘Noun’), 380), (Tag)

((‘말’, ‘Noun’), 370), (Word)

((‘페미니즘’, ‘Noun’), 363), (Feminism)

((‘여자’, ‘Noun’), 358), (Woman)

((‘더’, ‘Noun’), 333), (More)

((‘수’, ‘Noun’), 327), (Can)

((‘그’, ‘Noun’), 311), (That)

((‘남자’, ‘Noun’), 266), (Man)

((‘해시’, ‘Noun’), 264), (Hash)

((‘거’, ‘Noun’), 245), (Thing)

((‘차별’, ‘Noun’), 238), (Discrimination)

((‘때’, ‘Noun’), 214), (When)

((‘안’, ‘Noun’), 207), (Not)

((‘년’, ‘Noun’), 204), (Girl- derogatory term, but in this case often an appropriated term like it is the case in ‘slutwalk’)

((‘선언’, ‘Noun’), 198), (Declaration)

((‘일’, ‘Noun’), 192), (Work)

((‘남성’, ‘Noun’), 169), (Male)

((‘모든’, ‘Noun’), 167), (All)

((‘저’, ‘Noun’), 166), (I)

((‘평등’, ‘Noun’), 163), (Equality)

((‘생각’, ‘Noun’), 160), (Thought)

((‘우리’, ‘Noun’), 156), (We)

((‘날’, ‘Noun’), 154), (Me)

((‘뭐’, ‘Noun’), 152), (What)

((‘왜’, ‘Noun’), 150), (Why)

((‘트위터’, ‘Noun’), 147), (Twitter)

((‘운동’, ‘Noun’), 144), (Movement)

((‘사회’, ‘Noun’), 143), (Society)

((‘때문’, ‘Noun’), 138), (Because)

((‘지금’, ‘Noun’), 137), (Now)

((‘오늘’, ‘Noun’), 131), (Today)

((‘세상’, ‘Noun’), 126), (World)

((‘인간’, ‘Noun’), 125), (Human)

((‘게’, ‘Noun’), 119), (What)

((‘이유’, ‘Noun’), 119), (Reason)

((‘전’, ‘Noun’), 118), (Before)

((‘앞’, ‘Noun’), 117), (In front of)

((‘분’, ‘Noun’), 115), (Person)

((‘혐오’, ‘Noun’), 114), (Hate)

((‘좀’, ‘Noun’), 114), (A little)

((‘걸’, ‘Noun’), 113), (That)

((‘너무’, ‘Noun’), 111), (Too much)

((‘한국’, ‘Noun’), 107)] (Korea)

While there are interesting terms such as 차별[discrimination], 선언[declaration], 평등[equality], 운동[movement], and 혐오[hate], this is not yet enough to say something decisive about these tweets. A more detailed analysis would require comparison with other corpora (for example, tweets with other hashtags). I also would like to expand the analysis on the tweets with 페미니스트[feminist] OR 페미니즘[feminism].

References

Jang, Hayeon, Munhyong Kim, and Hyopil Shin. “KOSAC: A Full-fledged Korean Sentiment Analysis Corpus.” Sponsors: National Science Council, Executive Yuan, ROC Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica NCCU Office of Research and Development (2013): 366.

Eunjeong L. Park, Sungzoon Cho. “KoNLPy: Korean natural language processing in Python”, Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference on Human & Cognitive Language Technology, Chuncheon, Korea, Oct 2014.

World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2015. http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2015/the-global-gender-gap-index-2015/